How Pharmaceutical Companies Name Their Medications

What Goes Into a Drug Name: From Scientific Roots to Marketing Appeal

Table of Contents

- 1. Introduction: How Do Drugs Get Their Names?

- 2. The Evolution of Drug Naming (A Brief History and Origin)

- 3. The Three Types of Drug Names

- 4. The Importance of Unique Drug Names

- 5. The Drug Naming Process

- 6. Marketing & Branding Strategies in Naming Medication

- 7. The Power of Hybrid Drug Names

- d) Strategic Impact of Hybrid Names

- 8. Why Drugs Have Different Names in Different Countries

- 9. The Role of Domain Name & Global Branding

- 10. How Drug Naming Differs for Over-the-Counter (OTC) vs. Prescription Drugs

- 11.The Role of Patient & Doctor Feedback in Drug Naming

- Final Thoughts: Why Drug Naming Matters

1. Introduction: How Do Drugs Get Their Names?

Have you ever wondered how a drug gets its name? Why does Lipitor (Pfizer) sound powerful while Lyrica feels soothing? Why do some drugs have scientific-sounding names, while others are short, catchy, or futuristic? And why does the same medication sometimes have different names in different countries?

Naming a drug is far more complex than simply coming up with a marketable or scientific-sounding term. A drug name must pass strict regulatory approvals, align with branding strategies, and be linguistically tested to avoid confusion. It must also be distinct enough to prevent prescription errors while memorable enough for doctors, pharmacists, and consumers to recognize instantly.

A well-chosen drug name can significantly impact the lives of patients by ensuring they receive the correct medication.

So, who decides the generic and brand names of medications? Generic names are assigned by regulatory bodies such as the United States Adopted Names (USAN) Council and the World Health Organization’s International Nonproprietary Name (INN) system. These names follow strict guidelines, ensuring that similar drugs share recognizable endings (e.g., ”-mab” for monoclonal antibodies, ”-statin” for cholesterol-lowering drugs). Brand names, on the other hand, are created by pharmaceutical companies, who work with branding agencies, linguistic experts, and regulatory bodies to develop names that are scientifically relevant, unique, and marketable.

But why do drug names sound so complex and difficult to pronounce? The primary reason is safety—drug names must be distinct enough to prevent medication errors, especially when prescriptions are handwritten or spoken over the phone. Names that sound too similar to existing drugs can lead to life-threatening mistakes.

Another reason for complexity is global branding. A drug name must work across multiple languages and cultures, avoiding unintended meanings or associations that could hurt sales. This is why some drugs have different names in different countries—regulatory approvals, trademark conflicts, and linguistic sensitivities can force companies to modify names for different markets.

Finally, how do pharmaceutical companies come up with brand names for new drugs? The process involves blending scientific terminology, phonetics, psychology, and marketing strategies. A successful name must be:

✔ Easy to remember and pronounce

✔ Scientifically relevant

✔ Legally trademarkable

✔ Culturally appropriate for global markets

Pharmaceutical companies spend years developing and testing drug names, investing millions of dollars in the process. The right name can enhance brand recognition, drive market success, and even influence how doctors and patients perceive the drug.

In this guide, we’ll explore how pharmaceutical companies name their drugs—from the evolution of drug naming to the regulatory approval process, branding strategies, and global name variations. We’ll also take a deep dive into hybrid drug names, showing how companies blend science, marketing, and linguistics to create names that resonate.

By the end of this article, you’ll understand why naming a drug is one of the most critical decisions a pharmaceutical company makes—and how the right name can make or break a drug’s success.

2. The Evolution of Drug Naming (A Brief History and Origin)

While modern drug names follow strict regulations and branding strategies, pharmaceutical naming has evolved significantly over time. From early medicines named after their ingredients or effects to today’s complex scientific and trademarked brand names, the way drugs are named has changed to meet both medical and marketing needs.

Trademark conflicts have also played a significant role in shaping the evolution of drug naming, leading to more unique and distinguishable names to avoid legal issues.

Early Medicine: Naming Drugs by Ingredients and Effects

In ancient civilizations, medicines were often named based on their source, function, or appearance. For example, Opium comes from the Greek word opion, meaning “poppy juice,” since it was extracted from the poppy plant. Aspirin gets its name from Spiraea, the plant from which it was originally derived. Traditional remedies, such as Ginseng (meaning “man root” in Chinese), were named based on their shape or believed health benefits.

Before the 20th century, there were no universal naming conventions, leading to confusion and inconsistencies. The same drug could have multiple names depending on the region or culture using it. Additionally, linguistic sensitivities have influenced the naming of traditional remedies, ensuring that names were culturally appropriate and respectful.

The Rise of Scientific Drug Naming (19th & 20th Century)

As chemistry and pharmacology advanced, drug names became more structured. The introduction of chemical-based medications led to the creation of long, scientific names based on molecular structure. However, these names were too complex for doctors and patients to use effectively. For example, Acetylsalicylic acid, the chemical name for Aspirin, was difficult to pronounce and remember.

To improve consistency, regulatory agencies began developing standardized generic naming conventions. The United States Adopted Names (USAN) Council and the World Health Organization’s International Nonproprietary Name (INN) system established rules to ensure that similar drugs had recognizable suffixes.

For example:

• ”-olol” (Beta-blockers, e.g., Atenolol, Propranolol)

• ”-mab” (Monoclonal antibodies, e.g., Adalimumab, Infliximab)

• ”-statin” (Cholesterol-lowering drugs, e.g., Atorvastatin, Simvastatin)

These suffixes help doctors, pharmacists, and regulators quickly identify what type of drug they are dealing with.

The Modern Era: The Influence of Branding and Marketing (Late 20th Century – Today)

By the late 20th century, pharmaceutical companies realized that a drug’s success was tied to its name. Brand names needed to be distinctive, easy to pronounce, and marketable while still complying with regulatory guidelines.

This led to the rise of hybrid drug names that blend:

✔ Scientific credibility (referencing drug function or molecular structure)

✔ Phonetic appeal (names that are easy to say and remember)

✔ Emotional and psychological impact (names that feel trustworthy, effective, or powerful)

For example:

- Lipitor (Pfizer) → The name suggests “Lipid” (fat) + “Tor” (to block/lower), reinforcing its cholesterol-lowering function.

- Lyrica (Pfizer) → Has a soft, lyrical sound, which aligns with its use in nerve pain relief.

- Mounjaro (Eli Lilly) → Evokes a sense of great heights and achievement, reflecting its use in diabetes management.

As competition increased, companies also began conducting linguistic and phonetic tests to ensure that names were:

• Unique enough to be trademarked

• Easy to pronounce in multiple languages

• Not confused with existing drugs

Today, naming a drug is a multi-year process that involves regulatory agencies, branding firms, and linguistic experts to ensure it meets both safety standards and marketing goals.

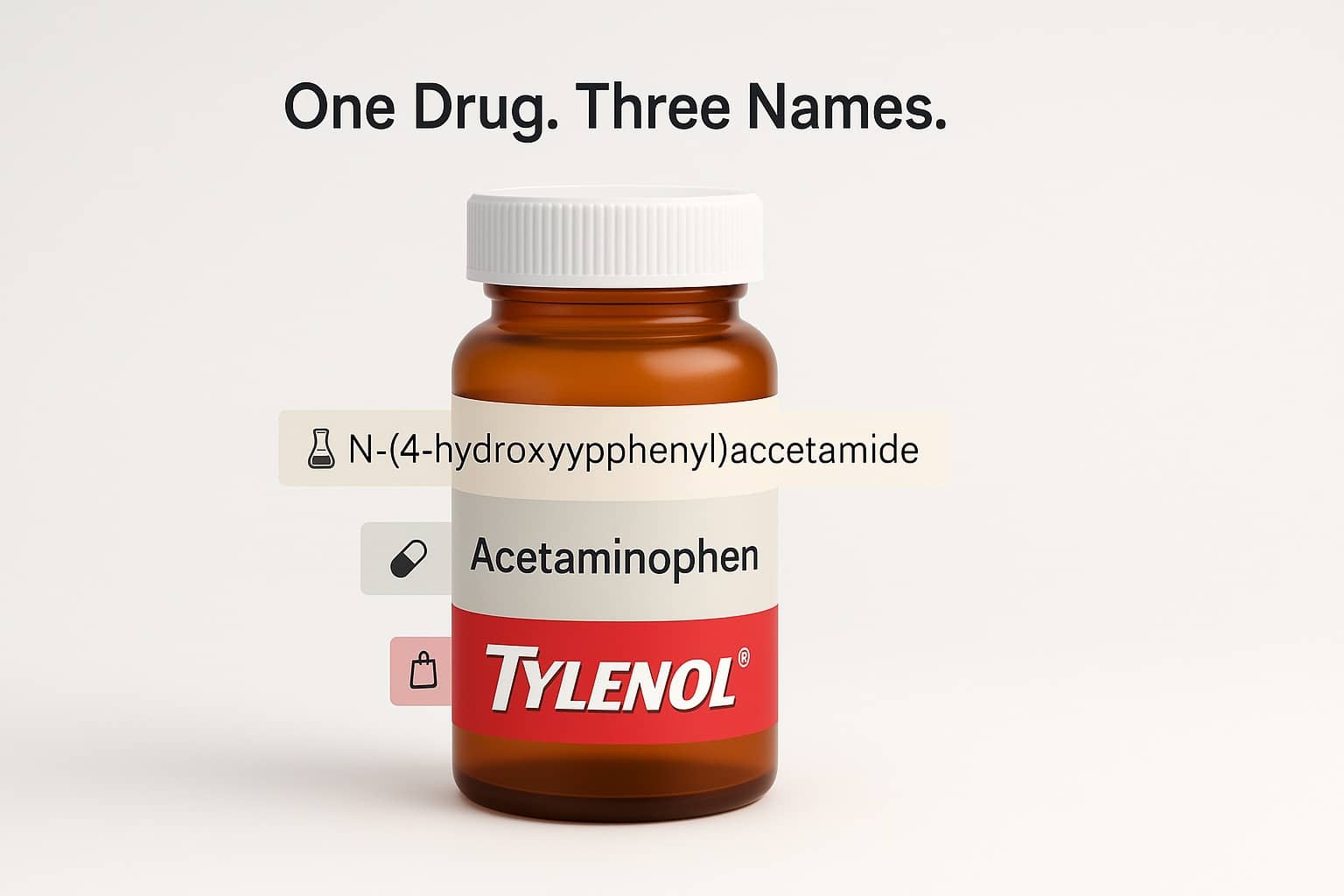

3. The Three Types of Drug Names

Pharmacists, along with other healthcare professionals, use three distinct names for every drug: a chemical name, a generic (nonproprietary) name, and a brand (proprietary) name. Each serves a different purpose, balancing scientific accuracy, regulatory compliance, and marketing appeal. Brand names often create a personal connection with patients, making them more likely to remember and trust the medication.

Understanding these three naming conventions is key to recognizing how drugs are classified, marketed, and prescribed worldwide.

a. Chemical Name: The Scientific Identity

The chemical name of a drug is its scientific description based on its molecular structure. These names follow International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) standards and are often long and complicated, making them impractical for doctors, pharmacists, and patients to use in everyday conversation.

For example, N-acetyl-p-aminophenol is the chemical name of acetaminophen, the active ingredient in Tylenol. Similarly, 2-(4-isobutylphenyl) propanoic acid is the chemical name for ibuprofen, found in Advil and Motrin.

Chemical names are only used in research and patents—they are not intended for public use due to their complexity.

b. Generic Name: The Universal Identifier for Patients

The generic name (also called the nonproprietary name) is assigned by regulatory bodies such as:

- The United States Adopted Names (USAN) Council (U.S.)

- The World Health Organization’s International Nonproprietary Names (INN) program (global)

- The European Medicines Agency (EMA) (Europe)

Generic names follow strict rules to ensure that drugs within the same class share common suffixes. These standard endings help doctors and pharmacists quickly recognize a drug’s therapeutic class and function.

Common Generic Drug Naming Patterns:

Generic names are consistent across all brands, meaning that regardless of the manufacturer, the active ingredient remains the same. This allows multiple pharmaceutical companies to produce and sell a drug under different brand names once its patent expires.

For example, Atorvastatin is the generic name for Lipitor, and Sildenafil is the generic name for Viagra.

c. Brand Name: The Marketable Identity of Brand Names

The brand name (also called the proprietary name) is the name created and trademarked by a pharmaceutical company. Unlike the chemical and generic names, the brand name is chosen for marketing, recognition, and memorability.

Brand names must be distinct from existing drugs, easy to pronounce, and appealing to both doctors and consumers. They also need to pass regulatory approval to ensure they:

✔ Do not sound too similar to another drug (to avoid prescription errors).

✔ Do not overpromise or mislead about the drug’s effects.

✔ Are culturally and linguistically appropriate for global markets.

Examples of Generic vs. Brand Names:

Brand names are typically designed to evoke certain emotions or associations to enhance marketability. For example:

- Lipitor → Sounds strong and authoritative, reinforcing its cholesterol-lowering effects.

- Lyrica → Has a soft, melodic sound, matching its use for nerve pain relief.

- Xarelto → Uses the letter “X”, making it sound high-tech and innovative, fitting for a blood thinner.

Once a brand-name drug’s patent expires, other companies can manufacture the same drug under its generic name, leading to the production of cheaper generic versions.

4. The Importance of Unique Drug Names

Ensuring Patient Safety

Unique drug names are not just a branding exercise; they are a critical component of patient safety. With thousands of medications on the market, having distinct names helps to avoid confusion and errors. This is particularly vital in areas where patients may have limited memory or cognitive abilities, making it challenging to distinguish between similar-sounding medications. For instance, a patient with memory issues might easily confuse two drugs with similar names, leading to potentially dangerous medication errors. Unique names help healthcare professionals, pharmacists, and patients to identify the correct medication quickly and accurately, thereby reducing the risk of mistakes and ensuring that patients receive the right treatment.

Branding and Marketing

In the competitive world of pharmaceuticals, a unique drug name can make all the difference. A distinctive name helps a medication stand out in a crowded market, making it more memorable for both patients and healthcare professionals. Effective branding can significantly influence patient preferences and prescribing habits, contributing to a medication’s success. A strong, unique name can establish a robust brand identity, setting a pharmaceutical company apart from its competitors. For example, a name that evokes a sense of trust and efficacy can make patients more likely to choose that medication over others. In essence, a unique drug name is not just a label; it’s a powerful tool for effective marketing and patient engagement.

5. The Drug Naming Process

Regulatory Guidelines and Approval

The process of naming a drug is far from arbitrary; it involves rigorous evaluation by regulatory bodies to ensure that the name is safe, unique, and compliant with regulatory guidelines. In the United States, the FDA is responsible for approving drug names. The agency meticulously reviews proposed names to ensure they do not sound similar to other drugs, are not easily confused with other medications, and do not contain any misleading or promotional language. The FDA also considers the origin of the name, ensuring it is not derived from a substance or word that could be misleading or confusing.

For example, in September 2019, the FDA announced new guidelines for naming biological products, including biosimilars, to reduce confusion and ensure patient safety. Similarly, the agency has taken steps to address the vaping epidemic by regulating nicotine-containing products and ensuring that their names do not appeal to youth. By following these stringent guidelines, pharmaceutical companies can ensure that their drug names are unique, safe, and compliant with regulatory requirements. This rigorous process ultimately contributes to better patient outcomes and improved public health, ensuring that drug names are not just marketable but also safe and effective for patients.

Who Approves Drug Names?

Several regulatory agencies oversee the approval and standardization of drug names. The primary agencies include:

- FDA (United States) → Oversees brand-name drug approvals through the Division of Medication Error Prevention and Analysis (DMEPA) to ensure names are distinct, safe, and not misleading.

- EMA (Europe) → Reviews drug names to prevent phonetic and visual similarities with existing drugs across multiple languages in the European Union.

- MHRA (UK) → Ensures drug names are safe, culturally appropriate, and distinct for the UK market.

- TGA (Australia) → Regulates pharmaceutical names under the Therapeutic Goods Administration, ensuring compliance with global standards.

- WHO (Global) → Through the International Nonproprietary Names (INN) system, the WHO standardizes generic names worldwide.

Each agency conducts rigorous testing to ensure that drug names do not sound too similar to existing medications, reducing the risk of prescription mix-ups.

How Long Does the Drug Name Approval Process Take?

The entire naming and approval process can take several years. A pharmaceutical company typically submits multiple potential names (often 3–5 options), knowing that some will be rejected.

- Preliminary Research (1-2 years) → Internal teams, branding agencies, and legal experts develop, test, and refine name candidates.

- Regulatory Submission (6-12 months) → The proposed names are submitted for approval to agencies like the FDA, EMA, and WHO.

- Phonetic & Safety Testing (3-6 months) → Agencies perform linguistic analysis, trademark checks, and sound-alike risk assessments.

- Final Approval (6-12 months) → A name is either approved, rejected, or requested for modification, requiring further rounds of submission.

Why Drug Names Get Rejected

Regulatory agencies reject drug names for several key reasons, including:

a. Sound-Alike and Look-Alike Errors (LASA Risks)

Drugs with similar-sounding or visually similar names can lead to life-threatening prescription errors.

Example:

- Losec (original name for Prilosec) was rejected because it sounded too similar to Lasix, a diuretic medication.

- Brintellix (an antidepressant) was renamed Trintellix in the U.S. to avoid confusion with Brilinta, a blood thinner.

Regulatory agencies conduct computerized phonetic analysis and test how names sound when spoken aloud, particularly over the phone in emergency situations.

b. Overpromising or Misleading Names

Drug names cannot imply an exaggerated benefit or be misleading about what the drug does.

Example:

- A drug name containing “Cure” or “Safe” would likely be rejected for suggesting a guaranteed outcome.

- Prevacid (acid reflux drug) was almost rejected because “Prev-“ implies prevention, but it does not prevent acid reflux—only treats it.

c. Trademark Conflicts & Legal Issues

Pharmaceutical companies must ensure their brand names do not infringe on existing trademarks.

Example:

- Nexium (AstraZeneca) was chosen over other names because “Nex-” implied “next-generation,” but it was still distinct enough to be trademarked.

- Zantac (Ranitidine) was named carefully to avoid conflicts with similar-sounding brands.

Drug companies hire trademark lawyers to conduct global searches and prevent costly legal disputes that could delay a drug’s release.

d. Linguistic & Cultural Issues in Global Markets

A drug name must undergo linguistic testing to ensure it is easy to pronounce in multiple languages and avoid offensive or confusing meanings in different cultures.

The chemotherapy drug Zelboraf had to be tested across multiple languages to ensure it did not resemble any offensive words.

FluMist (nasal flu vaccine) was carefully named to be clear and accessible to a global audience.

What Happens If a Drug Name Is Rejected?

If a drug name is rejected, the pharmaceutical company must:

✔ Revise and resubmit new names to the regulatory agency.

✔ Adjust pronunciation, spelling, or branding elements to make it more distinct.

✔ Undergo additional phonetic and linguistic safety testing.

Since the naming process takes years, companies often prepare backup names to avoid costly delays.

6. Marketing & Branding Strategies in Naming Medication

Pharmaceutical companies don’t just create scientific and regulatory-compliant names—they craft names that persuade, build trust, and enhance brand identity. A well-chosen name helps a drug stand out in a crowded market, influences doctor prescribing behavior, and even affects how patients perceive treatment effectiveness.

Unlike generic names, which follow strict scientific classification, brand names must resonate emotionally, be easy to pronounce, and differentiate from competitors. That’s why drug makers invest millions of dollars in naming agencies, linguistic testing, and consumer research before finalizing a name.

How Brand Names Influence Market Success

Pharmaceutical branding is about more than just making a name sound appealing—it’s about creating an identity that resonates with the target audience. A strong brand name can:

✔ Create trust and credibility – Names that sound scientific, authoritative, or innovative increase confidence in the medication.

✔ Evoke emotions and patient connection – A drug name can suggest comfort, relief, or transformation, affecting patient perception.

✔ Improve memorability for doctors and patients – A name that is easy to recall increases prescription likelihood.

✔ Differentiate from competitors – In highly competitive drug categories, a distinctive name can help boost market share.

For example, consider Lyrica, a nerve pain medication from Pfizer. The name has a soft, melodic quality, evoking a sense of calm and relief, which aligns perfectly with its intended use. In contrast, Xarelto, a blood thinner, incorporates the letter “X”, making it sound more high-tech and innovative—a common trend in modern pharmaceutical branding.

Phonetics & Memorability: Why Drug Names Sound the Way They Do

Pharmaceutical companies carefully construct the sound of a drug name to ensure it conveys the right message. Different phonetic choices can evoke different emotions and associations.

a. Strong & Authoritative Names

Names containing hard consonants like X, Z, and K often sound powerful and futuristic, making them suitable for high-tech, cutting-edge medications.

Examples:

- Xarelto (blood thinner)

- Zyrtec (antihistamine)

- Nexium (acid reflux)

These names create the perception of innovation and are more likely to be associated with advanced medical solutions.

b. Soft & Soothing Names

Names with soft sounds (e.g., L, M, R) create a gentle, calming effect, making them more suitable for pain relief or chronic conditions.

Examples:

- Lyrica (nerve pain)

- Humira (autoimmune diseases)

- Mounjaro (diabetes)

These names convey comfort, safety, and emotional support, helping patients feel more connected to the treatment.

c. Names Suggesting Action & Transformation

Some drug names are designed to subtly imply improvement, movement, or transformation, aligning with their intended effects.

Examples:

- Lipitor (cholesterol-lowering) – Implies it targets lipids (fats) and controls them.

- Tamiflu (flu treatment) – Clearly associates with flu prevention and treatment.

- Januvia (diabetes) – Derived from Janus, the Roman god of transitions, implying a new beginning in diabetes care.

These names influence how doctors position the drug to patients, making them more likely to prescribe or recommend it.

The Role of Consumer Testing in Drug Naming

Before a drug name is finalized, pharmaceutical companies conduct extensive market research to ensure the name:

✔ Is easy to pronounce in multiple languages

✔ Does not have negative or offensive meanings in different cultures

✔ Feels trustworthy and credible to doctors and patients

✔ Does not resemble other drug names that could cause confusion

Drug manufacturers test names on doctors, pharmacists, and focus groups to see how people react to the name’s sound, spelling, and meaning.

Example:

When Eli Lilly developed Mounjaro, they likely tested whether the name felt aspirational and motivating, aligning with its use for diabetes and weight loss.

In contrast, a poorly chosen name can cause confusion or negative associations, potentially hurting sales and patient adherence.

How Companies Differentiate Similar Drugs in the Same Category

When multiple competing drugs treat the same condition, branding becomes even more critical.

For example, consider the cholesterol-lowering drug category (statins):

- Lipitor (Pfizer) – Sounds strong and dominant.

- Crestor (AstraZeneca) – Suggests “crest,” implying peak performance.

- Zocor (Merck) – Uses hard consonants to convey strength.

Each name is carefully designed to feel powerful and trustworthy, while still sounding distinct enough to be memorable.

Similarly, in the GLP-1 diabetes/weight loss drug category, names follow a futuristic and aspirational trend:

- Ozempic (Novo Nordisk) – Sounds sleek and cutting-edge.

- Mounjaro (Eli Lilly) – Implies a high peak or great achievement.

- Wegovy (Novo Nordisk) – Has a friendly and approachable tone.

By ensuring names feel different yet competitive, pharmaceutical companies maximize their brand positioning in the market.

Brand Naming Challenges: When a Name Hurts a Drug’s Success

A poorly chosen drug name can cause:

- Confusion with existing drugs (leading to misprescriptions).

- Negative consumer associations (hurting sales and adherence).

- Rejection by regulatory agencies, forcing costly rebranding.

Example:

- The antidepressant Brintellix was renamed Trintellix in the U.S. because doctors were confusing it with the blood thinner Brilinta.

- The acid reflux drug Losec was renamed Prilosec because it sounded too similar to Lasix, a diuretic.

These cases show that even well-developed names can fail if they are too similar to other drugs or create confusion.

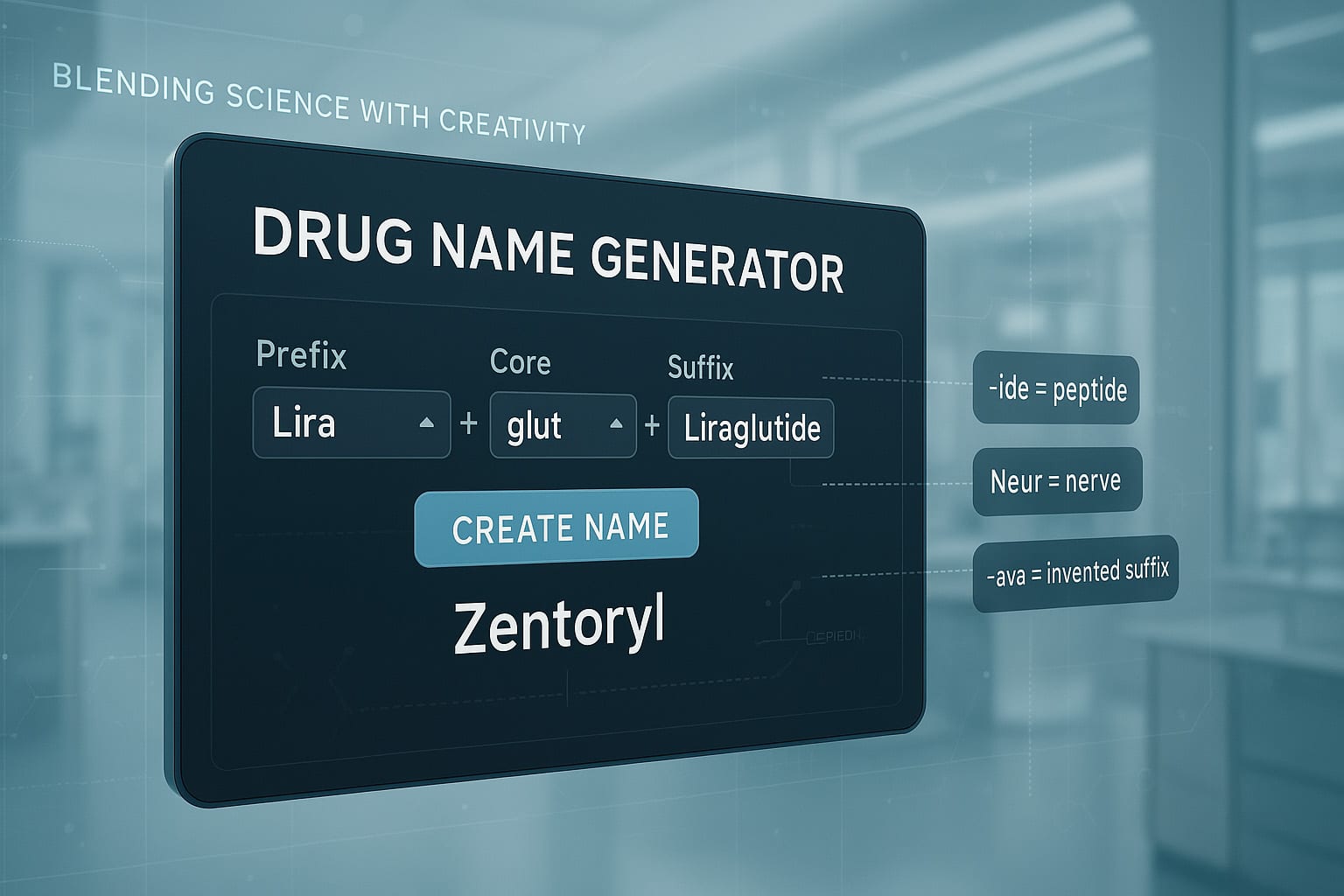

7. The Power of Hybrid Drug Names

One of the most effective strategies in pharmaceutical branding is the creation of hybrid drug names. These names combine parts of scientific terminology, branding cues, and phonetic appeal to craft something that is both medically relevant and emotionally resonant. A hybrid name is carefully constructed to suggest a benefit or convey an image while remaining unique, pronounceable, and legally protectable.

a) Scientific and Functional Combinations

Many drug names draw from their mechanism of action, drug class, or molecular structure to create familiarity among healthcare professionals. By embedding medical terms into the name, these drugs signal credibility and function.

Examples:

- Xeljanz (Pfizer) combines “Xel” (suggesting acceleration or healing) with “Janz,” a reference to Janus kinase, the enzyme it targets.

- Symbicort (AstraZeneca) blends “Symbi” (referring to synergy or combination) with “Cort” (corticosteroid), pointing to its dual mechanism for treating asthma and COPD.

These combinations make the drug’s purpose easier to recall and reinforce trust among prescribers.

b) Emotional and Aspirational Naming

Some hybrid names focus less on scientific language and more on how the name feels emotionally or what image it evokes in the consumer’s mind.

Examples:

- Skyrizi (AbbVie) evokes the image of a clear sky, suggesting freedom, clarity, and relief for people suffering from skin conditions like psoriasis.

- Mounjaro (Eli Lilly) is inspired by Mount Kilimanjaro, hinting at strength, elevation, and reaching new heights—fitting for a diabetes medication marketed with weight loss benefits.

- Verquvo (Bayer) combines “Ver” (from Latin for truth or strength) with a modern suffix that suggests movement, aligning with its use in heart failure treatment.

These names are designed to create positive associations and emotional engagement, even if the exact function of the drug isn’t immediately obvious from the name.

c) Creating a Futuristic or Innovative Sound

Drugs in competitive or high-tech categories often have names that sound advanced, sleek, or cutting-edge. The use of letters like X, Z, or V creates a sense of innovation.

Examples:

- Zykadia (Novartis), an oncology drug, uses the “Zy” prefix to sound modern and bold.

- Wegovy (Novo Nordisk) feels fresh and forward-thinking, matching its positioning in the fast-evolving weight loss market.

- Xofluza (Roche) uses “Xo” and “fluza” to sound like an exclusive flu solution, which it is—a next-generation antiviral flu treatment.

These types of hybrid names are particularly useful in fields like oncology, endocrinology, and neurology where breakthrough innovation is a core part of the product narrative.

d) Strategic Impact of Hybrid Names

Hybrid names help pharmaceutical companies:

- Differentiate their drug from competitors

- Communicate scientific relevance or therapeutic intent

- Enhance memorability among both clinicians and consumers

- Build long-term brand equity that extends beyond the patent period

A well-crafted hybrid name doesn’t just describe the drug—it tells a story that connects with both healthcare professionals and patients.

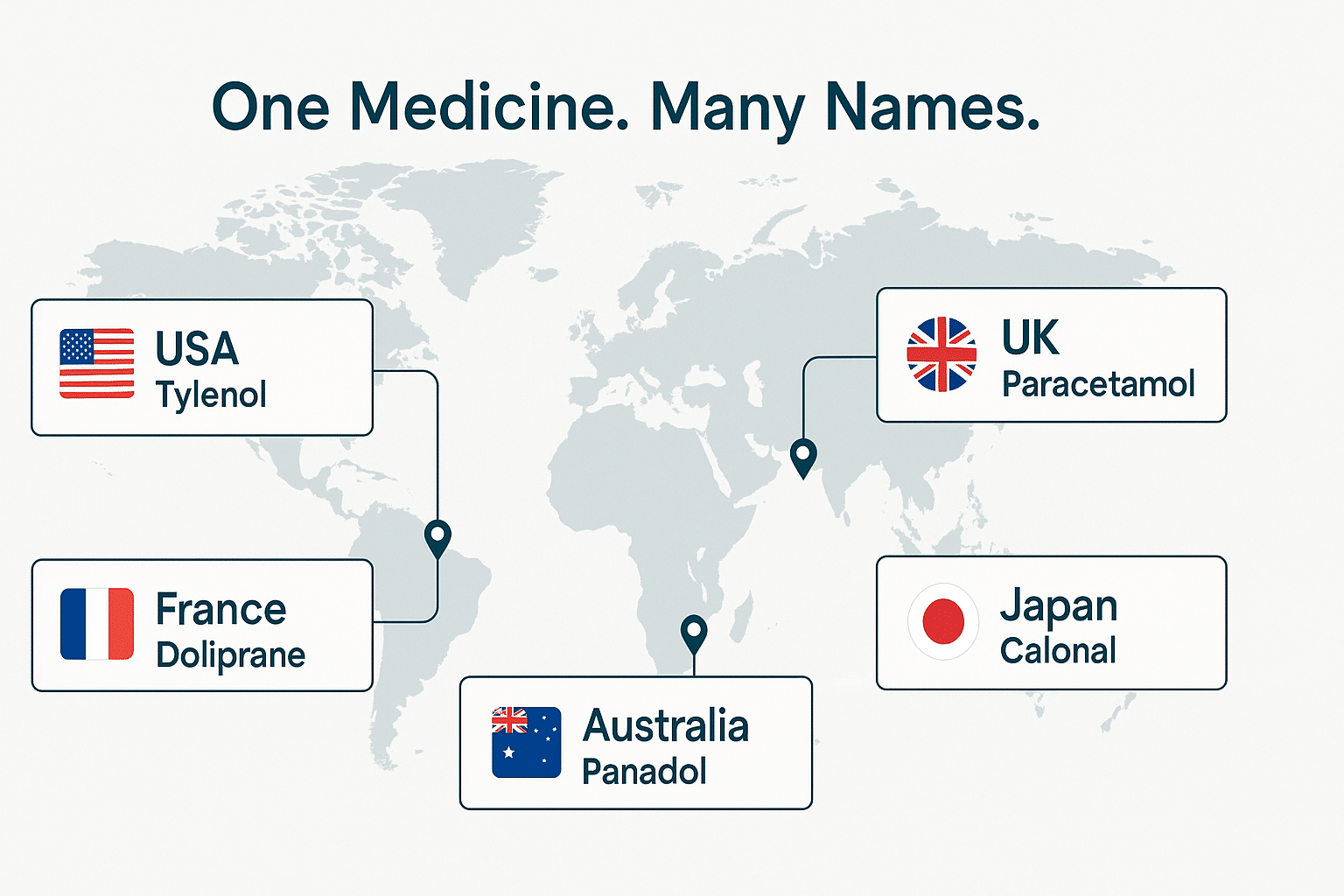

8. Why Drugs Have Different Names in Different Countries

It’s not uncommon for the same pharmaceutical product to be sold under different brand names in various countries due to trademark availability. Even when the active ingredient and formulation are identical, a drug may have one name in the United States and a completely different name in Europe, Australia, or Asia. These variations are not random—they reflect a mix of regulatory, legal, linguistic, and marketing considerations.

a) Trademark Conflicts

One of the most common reasons for a name change across regions is trademark availability. Pharmaceutical companies must secure exclusive rights to a brand name in every country they plan to operate in. If the proposed name is already trademarked by another company in a specific country—or is too similar to an existing trademark—it cannot be used there.

Examples:

- Eliquis (Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer) is known under its generic name, Apixaban, in some international markets due to brand name restrictions.

- Zocor (Merck), a cholesterol-lowering medication, was marketed as Lipex in Australia and New Zealand to avoid trademark conflicts.

- Nexium (AstraZeneca), a common heartburn medication, is called Nexiam in South Africa because the original name was unavailable.

Trademark laws vary by country, and companies often face the challenge of finding globally available names that are both unique and suitable for healthcare branding.

b) Linguistic and Cultural Adaptations

Even when a trademark is available, companies may still opt to change a drug’s name to suit local languages, cultural expectations, or pronunciation ease. A name that works well in English may be awkward, hard to pronounce, or even offensive in another language.

Examples:

- Brilinta (AstraZeneca), a blood thinner, is called Brilique in French- and Spanish-speaking markets, where the “-inta” suffix is less familiar.

- Zyrtec (U.S.) is sold as Zirtek in several European countries due to regional spelling and phonetic preferences.

- Allegra (U.S.) is known as Telfast in Australia and the UK, where a different branding approach was deemed more effective.

Pharmaceutical companies often conduct thorough linguistic testing to avoid name misinterpretation across multiple languages.

c) Local Branding Strategies

Sometimes a name is changed for purely strategic reasons, even when it’s legally available and linguistically neutral. This could be due to local branding strategies, how the brand will be positioned in the market, differences in consumer behavior, or competition in that region.

Examples:

- Losec (AstraZeneca) was renamed Prilosec in the U.S. because Losec was considered too similar to Lasix, raising safety concerns over name confusion.

- Fluoxetine is widely known as Prozac (Eli Lilly) in the U.S., but in some countries, it’s sold under different local brand names tailored to that market’s preferences or regulations.

By customizing names for regional markets, companies can better connect with local consumers, avoid competitive overlaps, and boost recall in culturally appropriate ways.

d) Case Study: Eliquis (Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer)

Eliquis, a widely used anticoagulant, has experienced naming and branding differences across markets due to regulatory reasons. While its brand name remains consistent in major markets like the U.S. and much of Europe, in some countries where Eliquis wasn’t available as a trademark, the drug is promoted using its generic name, Apixaban. This approach ensures continuity in prescription and pharmacist familiarity, even if the brand identity varies.

This example illustrates how a company may need to adjust its branding approach while still maintaining product integrity and consistency in medical communication.

9. The Role of Domain Name & Global Branding

In today’s digital-first environment, a drug’s online presence is just as important as its packaging, clinical data, and regulatory approval. Pharmaceutical companies must consider the availability and protection of domain names, social media handles, and digital assets when selecting and launching a new drug name. Failing to secure these can lead to brand dilution, misinformation, or even lost sales due to counterfeit or unofficial websites.

a) Why Domain Names Matter

Before launching a drug, most companies preemptively register domain names that match or closely resemble the drug’s brand name, which is crucial for digital branding. This includes .com domains, country-specific extensions (like .co.uk or .de), and even common misspellings.

Owning the relevant domain names helps:

- Prevent cybersquatting by unauthorized parties

- Direct patients and healthcare providers to trusted information sources

- Maintain consistent global branding across digital channels

For example, when Roche launched Tamiflu (Roche), the company secured tamiflu.com and related domains to prevent counterfeit sellers and unauthorized information from spreading online.

b) The Risk of Cybersquatting and Counterfeits

Cybersquatting refers to when a third party registers a domain name that matches a known brand, often with the intent of reselling it at a high price or using it to deceive consumers. In pharmaceuticals, this can lead to serious consequences—including the distribution of counterfeit drugs.

Examples of past issues include:

- Pfizer having to take legal action to reclaim domain names linked to its popular erectile dysfunction drug

- Eli Lilly working to shut down unauthorized websites selling fake versions of its medications

- Gilead securing Truvada-related domains during its HIV drug launch to avoid black-market activity

By anticipating these threats, companies can better protect their drug’s reputation and ensure consumers are accessing accurate information.

c) Building a Cohesive Digital Brand

Pharmaceutical companies also invest in building official drug websites that are educational, compliant with regulatory guidelines, and designed to support both prescribers and patients. These websites may include:

- Dosage and prescribing information

- Safety and side effect disclosures

- Patient support programs or savings offers

In addition to websites, companies often register relevant social media handles—even if they don’t plan to use them actively—just to prevent impersonation.

Eliquis (Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer), for example, has a strong digital presence that includes a dedicated website, paid search ads, and verified accounts to ensure patients and physicians are directed to trustworthy content.

d) The Role of Trademarks in Global Branding

A trademark protects the brand name from being used by others and allows the company to build equity around the name. Trademarks are filed in each country or region where the drug will be sold and must not conflict with other products.

Registering a trademark ensures:

- The name can’t be used by other companies or competitors

- Legal action can be taken if another party uses the name without permission

- The brand is protected from knockoff products and marketing confusion

Securing trademarks in parallel with domain names forms a complete global brand protection strategy.

e) Leveraging AI for Online Monitoring

Some pharmaceutical companies now use AI tools to monitor unauthorized domain activity, detect copycat websites, and identify mentions of their drug names across the web. These systems scan newly registered domains, detect patterns of potential abuse, and alert brand teams to take corrective action early.

This proactive digital vigilance is critical in ensuring patient safety and maintaining trust in the brand.

10. How Drug Naming Differs for Over-the-Counter (OTC) vs. Prescription Drugs

While prescription drugs and over-the-counter (OTC) medications may share similar regulatory scrutiny in terms of safety and efficacy, the way their names are created and marketed differs significantly. This is because the target audience, communication channels, and branding goals are very different for each category.

a) Target Audience and Communication Style

Prescription drug names are typically aimed at healthcare professionals—doctors, specialists, pharmacists—who are trained to recognize and understand complex naming conventions. These names can afford to be more technical, scientific, or abstract because they are usually explained in a clinical setting.

OTC drug names, by contrast, are targeted directly at consumers who may not have any medical background. As a result, these names are intentionally simpler, easier to pronounce, and more suggestive of the product’s purpose or benefit.

Examples:

- Acetaminophen is the generic name for Tylenol (Johnson & Johnson), a widely used OTC pain reliever.

- Loratadine is the generic name for Claritin (Bayer), an OTC antihistamine.

- Ibuprofen is sold under OTC brand names like Advil (Pfizer) and Nurofen (Reckitt).

OTC names often use everyday language or familiar-sounding syllables that convey relief, comfort, or reliability.

b) Branding Objectives

OTC products need to stand out on crowded retail shelves and compete directly for consumer attention. This requires branding that immediately communicates what the product is for, who it’s for, and why it’s different from competitors.

As a result, OTC names often:

- Use clear, benefit-driven language

- Avoid complicated or scientific roots

- Reinforce ease of use or symptom relief

Prescription drugs, on the other hand, are often marketed through professional channels and don’t face the same in-store pressures. Their branding focuses more on innovation, mechanism of action, and scientific credibility.

c) Regulatory Environment

Prescription drug names must be approved by agencies like the FDA or EMA to ensure they don’t mislead patients or resemble existing medications. OTC names, while also subject to regulation, are typically reviewed in the context of consumer safety, packaging claims, and advertising language.

Because OTC drugs are often older, generic medications repackaged for consumer sale, the brand names are crafted more with marketing in mind than scientific signaling.

d) Rebranding When Drugs Switch from Prescription to OTC

Many drugs that start as prescription-only later become available over the counter. When this happens, their names are often simplified or extended to make them more appealing and accessible to consumers.

Example:

- Nexium (AstraZeneca), a prescription medication for acid reflux, became Nexium 24HR when it was approved for OTC use. The updated name clearly communicates the duration of effect, which is important for shoppers making fast decisions at the pharmacy.

This type of rebranding helps bridge the gap between clinical authority and consumer appeal, allowing the drug to succeed in both contexts.

11.The Role of Patient & Doctor Feedback in Drug Naming

While much of the drug naming process happens behind the scenes—involving branding agencies, legal teams, and regulatory bodies—real-world feedback from doctors and patients plays a critical role in shaping the final name. After all, these are the people who will be prescribing, recommending, or taking the drug. Their perceptions, ease of understanding, and emotional response can make or break the name’s success in the market.

a) Feedback from Healthcare Professionals

Doctors, pharmacists, and nurses are often included in the naming process through surveys, interviews, or focus groups. Their feedback helps determine whether a name:

- Is easy to say and spell during verbal communication

- Sounds too similar to another drug, increasing the risk of confusion

- Appropriately reflects the drug’s purpose or class

Names that are too ambiguous, too complex, or too similar to existing medications can lead to prescription errors, delays in treatment, or mistrust.

Example:

Xarelto (Bayer & Johnson & Johnson), a blood thinner, went through multiple stages of testing with prescribers to ensure it could be easily remembered and clearly pronounced—especially important in high-risk cardiovascular care.

b) Consumer and Patient Testing

Patient panels are often used to test how well a name resonates emotionally. Pharmaceutical companies want to know:

- Does the name sound trustworthy?

- Is it intimidating, confusing, or too clinical?

- Does it imply comfort, relief, strength, or healing?

- Is the pronunciation straightforward for someone without medical training?

In some cases, a name that passes internal and regulatory review may still be rejected if patients respond negatively in testing.

Example:

Skyrizi (AbbVie), a drug for psoriasis, was developed with an emphasis on clarity and optimism. The name suggests openness and relief—feelings that align with the emotional experience of patients suffering from a visible and often stigmatized condition.

c) Avoiding Unintended Reactions

Cultural sensitivities and language barriers can turn a neutral or even positive-sounding name into something confusing or inappropriate. That’s why pharmaceutical companies also screen names across languages and cultures—often with the help of native speakers or local focus groups.

Names that suggest unpleasant associations or carry unintended slang or negative meanings in other markets may be dropped altogether, even if they work in the company’s home country.

d) Closing the Loop: Informing Brand Strategy

Feedback from both doctors and patients not only helps shape the final name, but also informs how the drug is positioned in marketing campaigns. A name that inspires trust or comfort can be further amplified in messaging. Conversely, if a name is found to create confusion or disconnect, brands can work on clarifying its value proposition in launch materials.

In this way, name testing becomes a foundational step in a broader strategy—ensuring that the brand is strong from day one, both in the clinic and in the consumer’s mind.

Final Thoughts: Why Drug Naming Matters

Naming a drug is far more than a branding exercise—it’s a strategic decision that impacts safety, trust, market positioning, and long-term success. The right name can make a new medication stand out in a competitive category, support accurate prescribing, and connect emotionally with patients and doctors alike.

Throughout the naming process, pharmaceutical companies must balance science, marketing, regulation, and linguistics. A great drug name needs to:

- Be scientifically appropriate and legally approved

- Avoid confusion with other products

- Resonate with prescribers and consumers

- Support digital branding and global scalability

We’ve explored how names are reviewed by regulators, crafted by brand strategists, tested with real users, and adapted for markets worldwide. We’ve also seen how hybrid names, domain protection, and OTC vs. prescription strategies all play into the final product’s identity.

In the end, a drug’s name is often its first impression—and in healthcare, that first impression can carry enormous weight. From saving lives to shaping trust, the name matters. A lot.